Blog

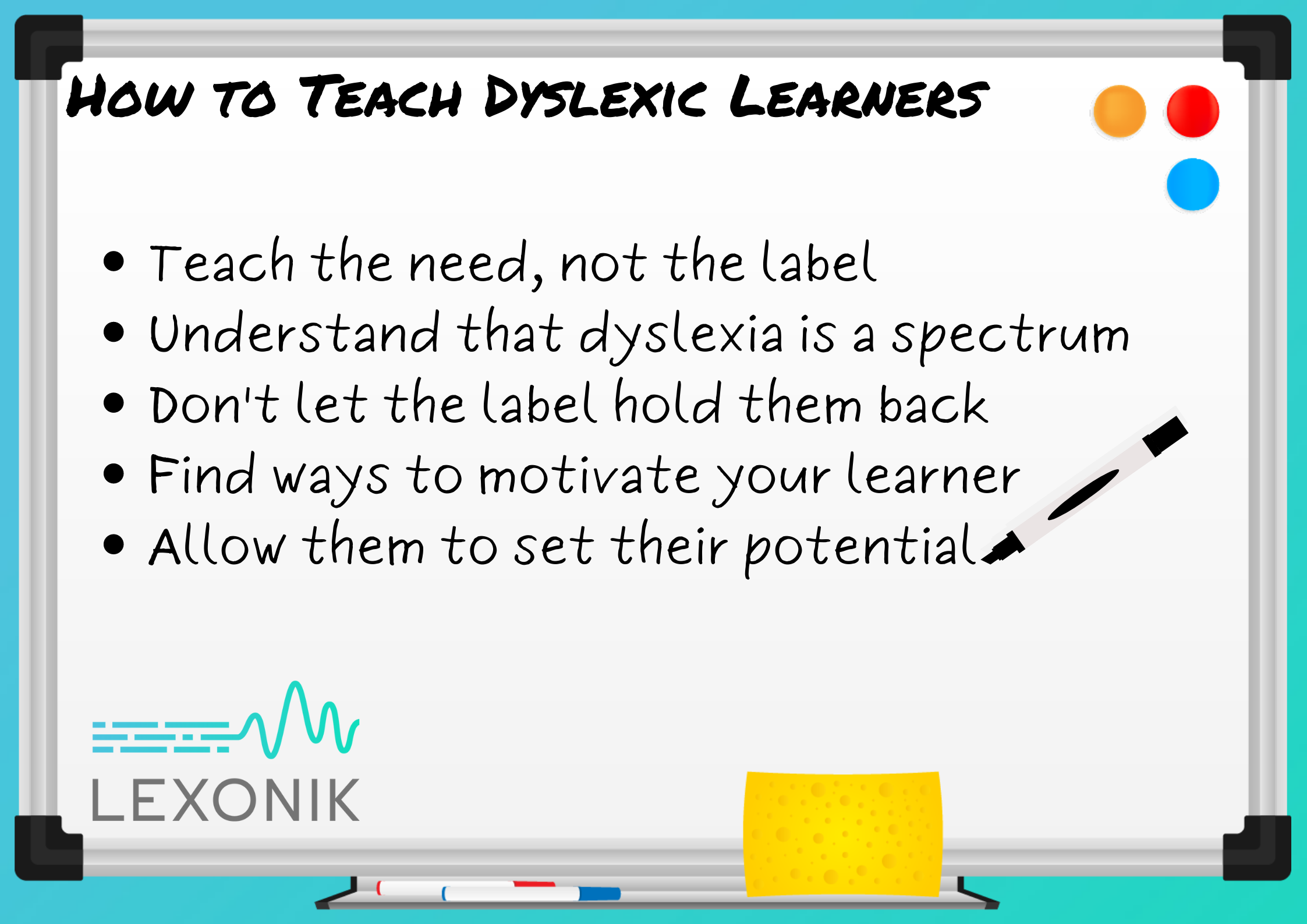

·How to Teach Dyslexic Students: Teach the Need, Not the Label

How to Teach Dyslexic Students: Teach the Need, Not the Label

Teaching dyslexic learners is no easy feat. Sometimes you need to convince them to work harder than other learners just to achieve the same results, or you may need to try alternative teaching methods and you have to do this without making the learner feel singled out or different.

Dyslexia is a learning disability that we are all still finding out in education. Where once upon a time, some children with dyslexia were considered slow or brushed under the rug with the phrase “I’m sure they’ll catch up”, but thankfully we are now seeing more awareness and support around the learning difficulty.

Because of this, we thought we’d offer some support of our own, by talking to a dyslexia specialist, former member of the British Dyslexia Association and Lexonik founder Katy Parkinson about her experiences working with and teaching dyslexic children.

Dyslexia is a spectrum

The first thing to remember when teaching dyslexic students is they are not a monolith. Just because learners have a diagnosis of dyslexia does not mean that they should be treated all the same. Katy spoke about the spectrum:

“Think of it as an umbrella and you’re somewhere on that spectrum - I am too.”

A weakness in reading, spelling, and writing are the common and professionally agreed traits of dyslexia. But outside of that it can affect learners differently. Some dyslexics may also struggle with organisation, concentration, visual perception difficulties or quality of handwriting, but these are in addition to their dyslexia. Dyslexia can affect everyone differently and the teaching approach needs to reflect that.

On an episode of the Vocabulary Detectives podcast the detectives spoke to dyslexic and master craftsman Philip Morley he illustrated this point when talking about his brother:

“My brother he's dyslexic too, but it's so different. He does OK academically, but if he tried to build a piece of furniture, he’d be a nightmare. He has no (practical) skills like trying to pass his driving test took him ten years, it's just a very different thing.”

Phil struggled with academics throughout his life, but found he had practical skills which he used to become a skilled craftsman. Meanwhile, his brother got by fine academically but struggled when it came to anything practical. This shows that when it comes to teaching learners with dyslexia, there is no easy, one-fits-all approach. Teachers need to tailor their approach around the learner, where they fall on the dyslexic spectrum and what skills they need the most support in developing.

Don’t make the label an anchor

At Lexonik we believe in teaching the need, not the label. But we do know why the label exists. The sad reality is too many hours are spent assessing whether or not a learner is dyslexic. This time could be better spent in devising a way to support that learner. But equally as Katy says:

“The label is necessary to gain funding, to get extra resources or perhaps a computer. Unfortunately, you need to have a specialist teacher or educational psychologist’s report to officially state you are dyslexic and entitled to extra time in exams and computers, voice recorders or whatever is deemed in the report that you actually need.”

The label is not insignificant in that regard and it’s also important to give the learner some peace of mind. It’s a huge relief for learners, especially young ones, to find out that it’s not their fault. They are not stupid or lazy and they have been paying attention. Phil spoke about his feelings before he found out he was dyslexic:

“I just kept on getting in fights and getting very frustrated and not really knowing what was going on. I knew I couldn't read. I couldn't spell. I was having a lot of difficulty.”

It was a huge relief for him to finally be assessed and told that he was dyslexic.

A huge amount of effort has gone into destigmatising the label as well, from places like the British Dyslexia Association and Succeed with Dyslexia to let people know that they are not alone and to educate the public on the disability.

That being said, it’s also important the label doesn’t make the learner feel singled out. They may need extra support or resources, and these are all things that will make them stand out in the classroom. This makes some learners feel very uncomfortable, awkward and sometimes angry.

However, there are ways to limit that feeling of otherness for any learner who is struggling with literacy. For example, let’s say you’re using Lexonik Advance to improve your learners’ spelling and reading. Introduce the programme with your top sets; it will still improve those top set pupils and, by doing it that way, you create a feeling of exclusivity. Don’t make learning feel like a punishment for the students who need it the most.

Motivate to educate

The label of dyslexia shouldn’t be used as an excuse. Katy spoke about seeing this:

“I've had it where I’ve assessed a child and said yes, your child is dyslexic and the reaction was oh, that's great then they don’t need to do anything now, because they’re dyslexic. So, they switch off and hide behind the label.”

This speaks to the issue of motivation, which can be quite tricky. In some cases, it involves convincing a learner to work twice as hard to be just as good as everybody else.

Motivating dyslexic learners can be done in several ways. Firstly, through the materials they use. For example, Succeed with Dyslexia advises the use of High/low books; as the name suggests, these are books that will have high interest for the learners actual age but low reading age as far as the content of the text goes.

We advise the use of Lexonik Leap and Advance, depending on the learners’ standardised score. This is because the morphemic analysis involved in these programmes will teach the learner how to break down other words going forward, because until their reading is reliable, they can’t access textbooks, worksheets and, therefore, any subject across the curriculum. The way our programmes are delivered can be beneficial to the dyslexic learner. Because the programmes are delivered in small groups, you get the benefit of giving the dyslexic learner more attention, while also making sure to assuage that aforementioned feeling of otherness.

The way you communicate with the learner is crucial. Katy makes it clear that you cannot heap all the responsibility on to the learner:

“If you use language like, ‘you need to work harder’ and point at them then you’re giving all the responsibility to the child. I would never, ever do that. Instead, I would say something like, ‘we need to work hard together. If we work together, if you work with me, we can do it’. It's always the word ‘we’. That word is so powerful.”

It needs to be clear that learning is a team effort and if your methods aren’t working, it needs to be clear that it isn’t their fault. Be clear with the learner and if you notice something isn't working for them tell them it’s you, the teacher, who’s going to have to make some changes to your teaching approach.

You also have to capitalise on the learners’ interests. Curriculums are varied and there’s bound to be something the learner engages with. If they hate English and maths but love P.E., then it’s a prime opportunity to introduce them to magazines or articles about their favourite sport. This will also be more accessible to them because they will have prior knowledge, as proven in The Baseball Study which states that if a weaker reader has more subject knowledge about a text’s subject matter, they will be able to comprehend it better than a stronger reader who doesn’t.

But more than that, excelling at something will be amazing for a dyslexic learner’s confidence. Phil proved this point when he talked about attending trade school:

“I did the trade school for three years and that was the first time I was told I was good at something. It was an amazing thing, you know? It was kind of silly in a way, but it's that's all I wanted to be told. I was told I was good at something, and I just jumped into it, and I loved every part of it.”

That praise was invaluable to Philip, but that praise must be genuine. A learner will pull back if they don’t feel they’ve done as good a job as you say. It hurts the trust in the relationship and makes them feel patronised. Finding something they’re interested in means they will take to it more naturally and you can use that as a platform for further learning.

Don’t cap their potential

Our final tip is simple: don’t let the dyslexia limit their potential. Don’t coddle them. Again, we say teach the need, not the label. Katy explains:

“If I let a student off with things and not expect too much of them, I have judged them in some way to be at that level. I’ve actually put an artificial cap on their ability, judging them not to be capable. Instead, what I should be saying is OK, let’s work at this; we will improve.”

Just because they are dyslexic doesn’t mean they can’t do things. It means it may be harder for them to do things. Don’t assume they can’t do certain things and don’t discount them from thriving. As we have said, it’s a spectrum and dyslexia can affect learners differently, so assumptions about their potential is something that needs to be avoided. It also speaks to the motivation of a dyslexic learner and building that trust is essential in getting them working. If they feel like you’re capping them, that violates the trust you’ve been building; they need to be lifted up and not kept at a certain limit.

Conclusion

So, there are our tips for teaching dyslexic learners. Be aware of the dyslexic spectrum, be aware of the label’s advantages and disadvantages, find ways to motivate and communicate effectively and never cap their potential.

If you’re looking for resources to help dyslexic learners, check out our literacy programmes or if you’re looking for advice, get in touch.