Blog

·Year 11s must leave school fully literate: from GCSEs and beyond

Think back to GCSE results day 2022. There was much anticipation and build-up about the first set of ‘proper’ exams since the Covid pandemic. But when the results actually came out there was a distinct feeling of box-checking happening.

There was a lot of talk of the north/south divide growing again and girls yet again outperforming boys. A focus on next year washed over us immediately: what do we need to do to make the numbers trend in a favourable direction next year? But there was very little thought for the 16-year-olds freshly released into society, now to fend for themselves.

What would happen to those who left without vital skills such as reading, writing and phonics? Almost 30% of students did not achieve a grade 4 or higher in their English GCSE in 2022; that is a just shy of a third of students leaving school without the everyday skills you need to understand bills, read to their children, or write job applications. Out of over 700,000 learners sitting English exams in 2022, over 200,000 did not pass. They now have to re-sit English this year, and with 71.6% of students not achieving a grade 4 or above in their English resit last year, these learners are in very real danger of being left behind.

The resit situation is something we at Lexonik are involved in remedying. The Department for Education has given us an expected 3-year grant to provide fully-funded professional development to colleges in the North East, Humber and Yorkshire. As well as training to deliver our intervention programmes Lexonik Leap and Advance, the plan is to upskill the educators at these institutions with dedicated training and access to our effective literacy intervention programmes. They will be able to utilise all of this to the betterment of post-16 learners, ensuring that the resit pass rate increases.

We’re proud to be doing this work. The chance to affect our community is invaluable to us and we know we can help learners gain essential skills before they go into the world of work. But we want to do more.

Addressing the low pass rate of post-16 resit exams is obviously important. We have to support post-16 provisions because the reality is, through no fault of the educators, that not every student will be ready by 16 years old. But is that 30% of all students sitting English GCSEs? We don’t think so. We think more can be done to stop so many students going into post-16 provisions, which should help the learners as their teachers should be able to dedicate more focus to smaller cohorts.

Besides that, a game of tit for tat between schools and colleges helps no one. Education is a collective and educators shouldn’t have the stance of us vs them. Students not passing GCSE isn’t necessarily to do with a lack of instruction at secondary, just as being behind in Y7 isn’t just to do with wobbles in Y6 teaching. We have to see education as a continuum because it’s society that puts time stamps on progress and achievement, and not the human brain or being.

Some people just aren’t ready for English and Maths GCSEs at age 16, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be ready for them in the future.

We can’t alter the entire education system - not least because no one wants their children to be in the experimental years - but we can alter how educators look at and view reading development and acknowledge the education continuum; if a human being isn’t ready for GCSE’s at Y11, then they can be continued to be helped until they are ready.

That being said, we can get as many students ready as possible in Y11, and also be there to continue that support and development post-16.

So, with that in mind, what can be done to get as many Y11s fully literate before they leave school? Firstly, we need to fully understand the gravity of the situation; what happens when students become adults without essential literacy skills such as reading, spelling, phonological awareness and comprehension. The National Literacy Trust says that 16.4% of adults in England alone have “very poor literacy skills” making them functionally illiterate.

The impact of this is detrimental in so many ways. Think about how much you have to read during a day and try to imagine not having that skill that you rely on so heavily. These are people who struggle every day - long words on medicine bottles don’t make sense to them, they may struggle to understand and therefore pay bills that come through the front door, and many of them can’t read a bedtime story to their children. This perpetuates a vicious cycle as The National Literacy Trust describes the benefits of reading to children during early development:

“By starting the journey of building a lifelong love of reading for pleasure, parents are giving their child the opportunity to be the best they can be: children who read for pleasure do better in a wide range of subjects at school and it also positively impacts children’s wellbeing.”

Children who are read to early do better academically and personally. So, parents who can’t give this gift to their children are more likely to see their children repeat this cycle. Potentially, generations of functionally illiterate adults following on from one other. That is the gravity of Year 11s leaving school and going into the world without these essential skills.

So now that’s understood, what can be done right now to help our learners leaving school? The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) published a guide on how best to improve secondary school literacy that had 7 key recommendations:

- Prioritise ‘disciplinary literacy’ across the curriculum

- Provide targeted vocabulary instruction in every subject

- Develop students’ ability to read complex academic texts

- Break down complex writing tasks

- Combine writing instruction with reading in every subject

- Provide opportunities for structured talk

- Provide high quality literacy interventions for struggling students

There’s a lot here that’s easier said than done. Some of these points cover how everyday lessons should be conducted, such as combining writing instruction with reading, breaking down complex writing tasks and providing opportunities for structured talks. An educator may need a little help in implementing some of these points across their school and that’s where we come in.

To get the obvious out of the way, Lexonik clearly hits recommendation 7 “Provide high quality literacy interventions for struggling students”. We have a range of intervention programmes to address every literacy need a learner might have. We work especially well with struggling students as proven by the National Literacy Trust impact evaluation study into Lexonik Advance, which states:

“The programme was particularly beneficial for students who began with decoding skills below the national average (n = 89). Their standardised scores increased from 78.0 before the programme to 91.5 afterwards, a slightly greater increase than we saw for the cohort overall (13.5 points vs. 11.5 points)”

However, you may be surprised at how well we address the other recommendations of the EEF’s guide. We have written about how Lexonik programmes can help emphasise disciplinary literacy, specifically in regard to addressing the postpandemic phonics gap. But it isn’t just our phonics intervention programme, Lexonik Leap, that can help with this. It’s our whole ideology. Lexonik programmes work on a basis of morphemic analysis, teaching prefixes and suffixes rather than whole words. This means if a student doesn’t know the word “fortification” but knows the morpheme “fort” meaning strengthen, “fic” meaning make into and “tion” meaning act, process or result, then they can use what they know to figure out what they don’t. Therefore, “fortification” must mean something to do with the process of making something strong.

This approach applies to both teachers and students when we offer training; it’s not just to English teachers. We can train any member of staff to practice this method and deliver our interventions.

We have tools available to emphasise disciplinary literacy. Lexonik Vocabulary Plus can function as a search engine for words, definitions and morphemes. Best of all, it’s available to every member of staff in the school with just one licence making breaking down and explaining complicated vocabulary in mathematics, geography, and just about any lesson in the curriculum, easier than ever. This also addresses recommendation 2 “Provide targeted literacy instruction in every subject” as teachers will have a tool to make designing activities involving any subject’s terminology easy.

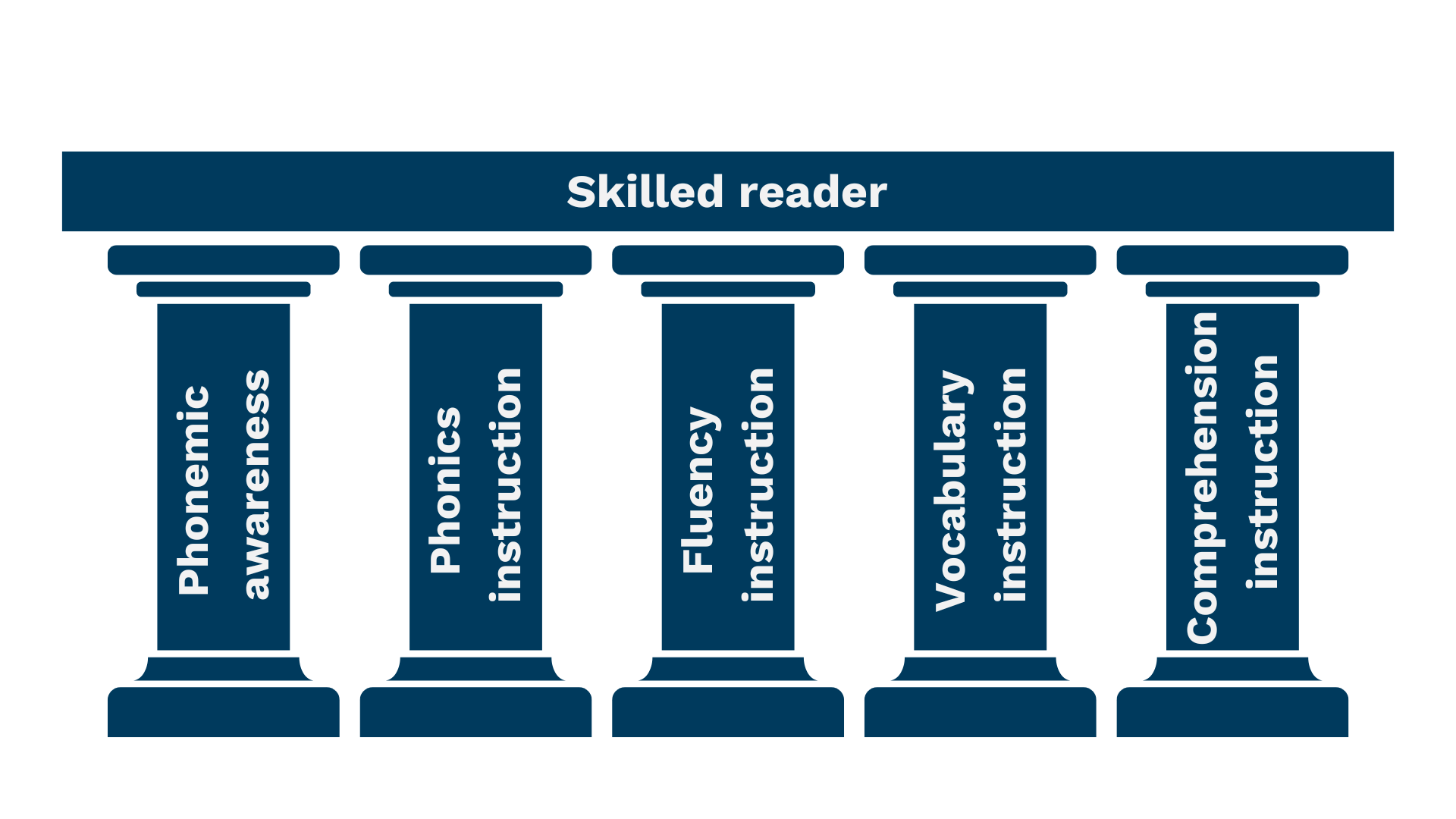

We understand that literacy is built up of a plethora of skills, which themselves are built up of several proficiencies. Like an onion of essential life skills, literacy has many layers. For example, at first glance, reading is one of the skills that make up literacy. But reading is built up of phonetic awareness, phonics instruction, vocabulary, comprehension and reading fluency. Then, on its own, reading fluency is built up of automaticity, prosody, comprehension and syllabification. It’s daunting! Therefore, recommendation 3 “Develop students’ ability to read complex academic texts” falls into the easier said than done category.

But don’t lose yourself in the layers, we can help with that too. Because literacy is so complicated, is the very reason we offer multiple literacy programmes. Our flagship programme Lexonik Advance covers a wide range of skills on its own. Northumbria University’s impact study of Advance found that the programme had, on average, a 27-month reading age gain for its participants, in just 6 weeks. With that kind of progress your learners will be well on their way to reading complex academic texts in no time!

Combine all of this with the fact that The National Literacy Trust, in the aforementioned impact study of Lexonik Advance, found that it was proven to work better with older students:

“Older students benefited from the programme more than younger students.

On average, standardised scores increased by 7.8 for those aged 11 to 12, by

11.5 for those aged 12 to 13, and by 15.4 for those aged 13 to 14”

Then we come to the conclusion that our targeted intervention programmes can help Year 11s gain the essential literacy skills needed before they leave school. We take pride in our programmes working for older students, as we took great care to develop them to be unpatronising and not talk down to learners, no matter their age. We think because of this, they engage more with the content of the programme; it’s vital that it doesn’t make them feel lesser than their peers.

If this approach appeals to you and you’re looking to help learners of any age develop their literacy skills, then please get in touch here or check out the full range of our literacy programmes to find which one best addresses the needs of students.